Microplastics and Your Heart Health.

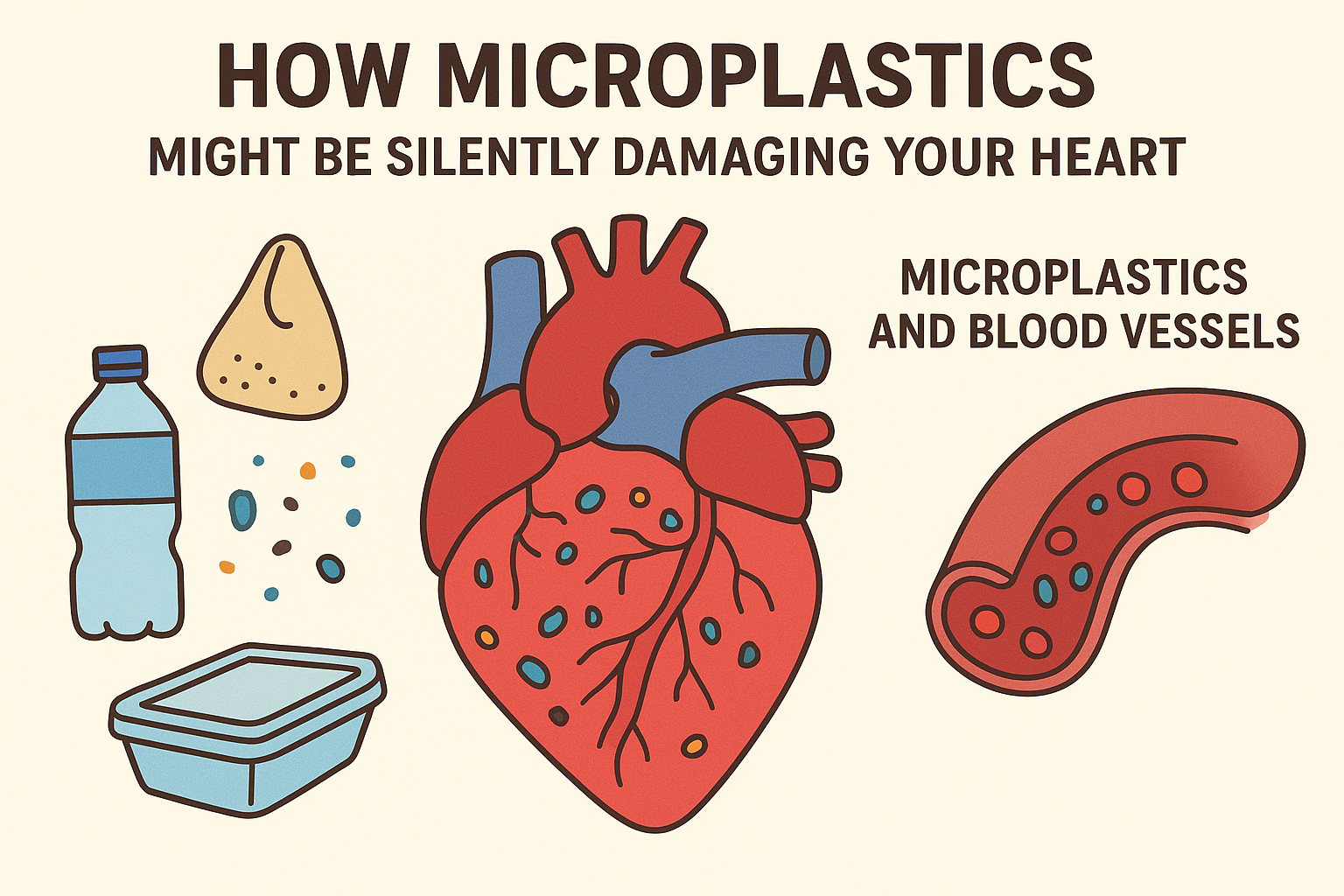

Microplastics, Blood Vessels, and Heart Disease

In recent years, micro- and nanoplastics have become an increasing concern in both environmental science and public health. Emerging research now suggests these particles may have direct implications for cardiovascular health. Several recent human studies have detected plastic particles embedded within arterial plaques, lodged in the walls of major blood vessels, and even present in heart tissue itself.

A landmark clinical study reported that individuals whose carotid artery plaques contained micro- or nanoplastics faced a significantly higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death over approximately three years compared to those without detectable plastics. This represents the first prospective evidence in humans that microplastic exposure may be linked to elevated cardiovascular risk — suggesting that the plastic pollution problem extends beyond the environment and into the circulatory system itself.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38446676/

Understanding Microplastics and Nanoplastics

Below, we outline what microplastics are, how they enter the human body, what current human evidence reveals, the most plausible biological mechanisms, and practical steps you can take to reduce exposure.

What Are Microplastics and Nanoplastics?

Microplastics are plastic fragments typically smaller than 5 millimeters (down to the micrometer scale), while nanoplastics are even tinier—generally less than 1 micrometer in size.

These particles are shed from countless everyday sources, including consumer products (like bottles and food containers), synthetic fabrics, vehicle tires, paints, and more. Due to their minute size, they can be both inhaled (from indoor dust or outdoor air) and ingested (through food, bottled water, seafood, table salt, or even tea brewed from plastic tea bags).

Once inside the body, a portion of these particles appears capable of crossing biological barriers, allowing them to enter the bloodstream and tissues. Recent systematic reviews (published in 2024) have reported detections of microplastics in multiple human tissues. However, these studies also highlight significant uncertainties—particularly in how microplastics are measured and what their true health impacts may be.

https://jogh.org/2024/jogh-14-04179

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/toxicology/articles/10.3389/ftox.2024.1479292/full

https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/45/38/4099/7750375

Direct Findings in Human Hearts and Arteries

Microplastics in Human Heart Tissue

In 2023, a pilot study involving patients undergoing cardiac surgery detected microplastics in multiple regions of the heart, as well as in perioperative blood samples. Although the study was small and exploratory, its findings provided compelling evidence that plastic particles can reach—and persist within—cardiac tissues.

The authors reported the presence of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) in the left atrial appendage, epicardial, and pericardial adipose tissues. They concluded that these detections could not be explained by accidental contamination during surgery, indicating that the microplastics were already present in the patients’ bodies prior to the procedure.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37440474/

Microplastics and Blood Vessels

In 2024, researchers reported the presence of microplastics in three major types of human arteries — the carotid (neck), coronary (heart), and aorta (the body’s main artery). Remarkably, microplastics were detected in all 17 arterial samples analyzed.

The study found that arteries containing atherosclerotic plaques—particularly the coronary and carotid arteries—had significantly higher concentrations of microplastics compared to plaque-free aortas. These findings suggest a possible association between microplastic accumulation and the development of atherosclerosis in humans.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37440474/

A Prospective Signal: Plastics in Plaque and Future Cardiovascular Events

The most robust human study to date — published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2024 — investigated the presence of micro- and nanoplastics in carotid endarterectomy specimens. The study included 257 participants who were followed for a median of 34 months after surgery. Importantly, all participants were undergoing the procedure for asymptomatic carotid artery disease.

Micro- and nanoplastics were detected within the carotid plaques of a subset of patients. Those with detectable plastics had a significantly higher risk of experiencing the composite endpoint of myocardial infarction (heart attack), stroke, or death from any cause compared with those whose plaques were free of plastics (hazard ratio 4.53; 95% CI, 2.00–10.27; p < 0.001).

While the findings do not establish causation, they provide the first prospective evidence in humans linking the presence of plastic particles in arterial plaques with an increased risk of subsequent cardiovascular events. This work suggests that micro- and nanoplastic exposure may represent a previously unrecognized contributor to cardiovascular risk.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38446676/

Summary

In summary, multiple independent research teams have now detected microplastics within human arteries, atherosclerotic plaques, and heart tissue. Moreover, at least one prospective clinical study has linked the presence of these particles in arterial plaques to higher risks of heart attack, stroke, and death.

As a result, the question of “microplastics and heart disease” has moved beyond speculation. It is now an active area of scientific investigation, supported by early but consequential human evidence.

Practical Current Advice for Clinicians and Patients

For Clinicians

The key message for clinicians is to prioritize management of established cardiovascular risk factors — including lowering LDL cholesterol, controlling blood pressure and glucose, supporting smoking cessation, promoting regular physical activity, and addressing sleep and stress. These remain the cornerstones of cardiovascular prevention. At the same time, clinicians should stay informed about emerging evidence on microplastics, as this area of research evolves rapidly.

For Patients

In addition to following standard heart health recommendations, patients may consider practical steps to minimize microplastic exposure. This includes reducing contact with hot plastics (e.g., avoid microwaving food in plastic containers), limiting use of single-use plastic bottles and packaging, and being cautious about unverified detox or “plastic-removal” products. Ultimately, the most effective protection for cardiovascular health remains well established: a Mediterranean-style diet, regular exercise, and proactive management of traditional risk factors — now perhaps complemented by more mindful plastic use.

Final Word

Evidence is accumulating that microplastics can reach human arteries and heart tissue. One prospective study has even linked their presence in arterial plaques to higher rates of heart attack, stroke, and death. Combined with plausible biological mechanisms, these findings have drawn legitimate interest from cardiologists and public health researchers alike.

However, the science is still evolving — key questions remain about dose–response relationships, long-term exposure, and causality. Further research will be crucial to clarify the true cardiovascular impact of microplastics.

For now, our focus should remain on proven preventive strategies, while keeping an open and evidence-based eye on this emerging field.

Notes on Interpretation

- Association does not equal causation.

- The strongest human evidence to date (NEJM, 2024) is observational, though prospective.

- More data are needed before firm clinical conclusions can be drawn.